When Typhoon Odette hit the Philippines, including Siargao island – a popular surfing destination – in December 2021, it killed hundreds and destroyed countless homes across the country. In the wake of the disaster, municipal governments set in motion relocation plans for those living in declared No-Build Zones, intended to reduce future climate and disaster impacts on communities by discouraging construction in areas at high risk of storm surges, flooding, and other hazards.

As climate change accelerates globally, planned relocation - a process that involves permanently moving entire communities from high-risk areas to designated new sites - is expected to increase. Some communities will plan their own relocations and request governmental support, while in other instances, governments may force relocation against residents’ wishes. When relocation is unavoidable – a last resort after all other efforts to adapt have failed – Human Rights Watch advocates for a rights-based approach that ensures affected communities, including people with disabilities, have a voice in the process.

International human rights law obligates governments to pursue these goals in a rights-respecting manner. According to international standards, climate change adaptation policies should not further harm affected communities and affected people should be informed, consulted, and able to participate in decision-making around climate-related planned relocations.

The plans implemented on Siargao island, however, were largely created without consulting with or providing information to the affected coastal and riverbank communities.

From February to September 2025, Human Rights Watch visited Siargao island multiple times to understand how people with disabilities experience climate-related risks and government responses to these risks. This interactive feature shares the stories of three women and a man, all local residents with disabilities. They describe how storms intensified by climate change have altered their lives, how government relocation decisions are made without their participation, and their hopes for their communities amid an increasingly uncertain future.

Their stories echo others we heard across the island. They also capture the experiences of other people in the Philippines and worldwide who have been displaced by the consequences of climate change—or who could be in the future.

“I cannot run like everyone else.” – Zenaida Tomines

Zenaida Tomines is a 52-year-old woman who has lived with her husband and 4 children in San Isidro, a municipality of Siargao island, for nearly two decades. She is a polio survivor who finds even short walks painful. She supports her family by catching crabs in the river by her home and selling them in the local market.

On the morning of December 16, 2021, their entire lives changed when a typhoon – locally called “Odette” and internationally known as “Rai” – struck the island.

Zenaida initially did not think Typhoon Odette would be different from other storms, but within hours, it intensified into a catastrophic cyclone beyond anyone’s expectations.

When Zenaida’s husband and children decided to take shelter at the evacuation center, she stayed behind. “I cannot run like everyone else, I need assistance to escape,” she said.

As the winds grew stronger with heavy rainfall, her husband, fearing for her life, returned on a motorcycle, lifted her onto it, and took her to the evacuation center.

Once the storm passed, Zenaida returned to the riverbank, where she found the remnants of their house. With no information about shelters or assistance, Zenaida and her family built a makeshift shelter where their home once stood.

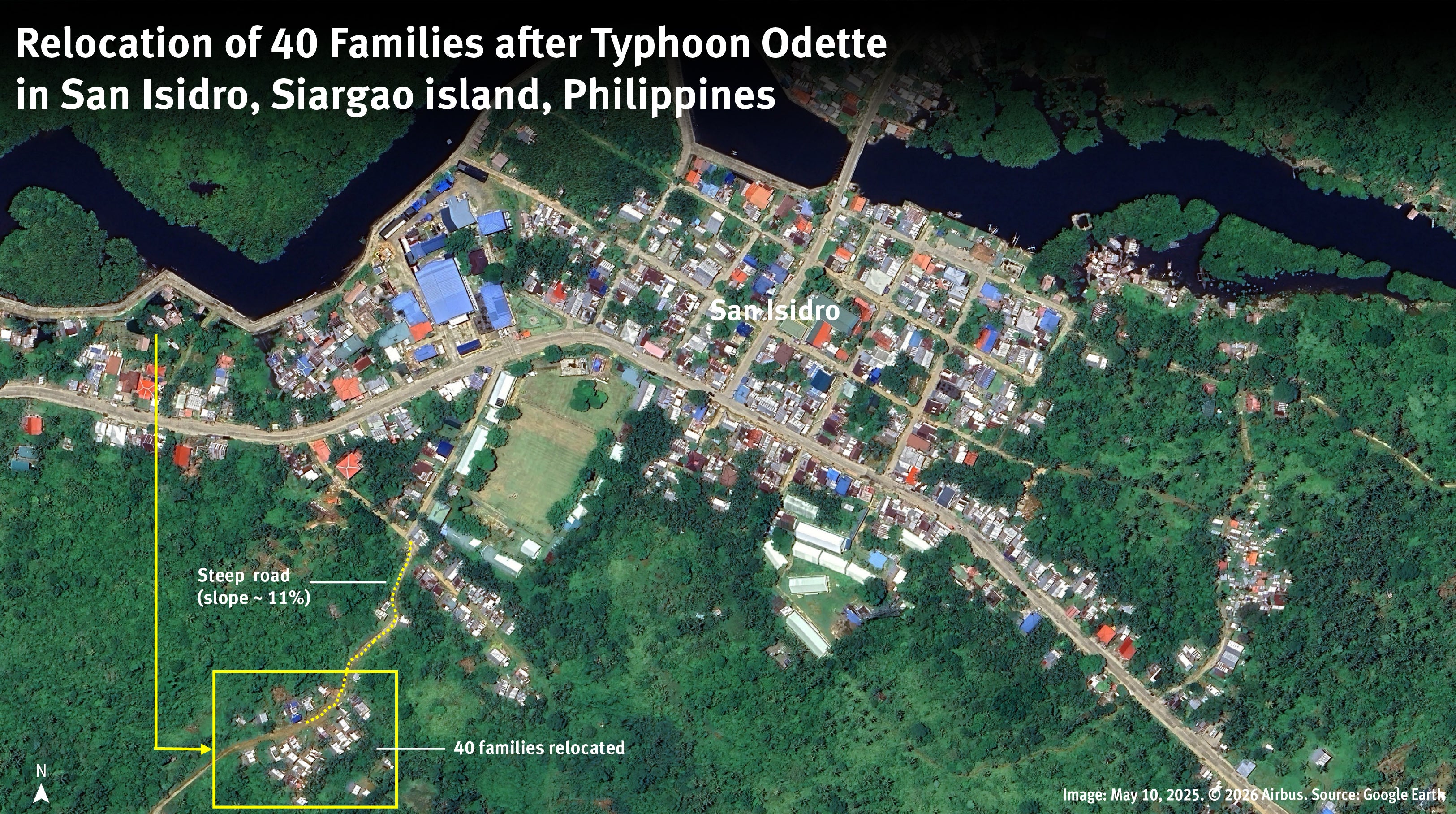

Days later, local officials told them to relocate uphill to what was described as a temporary site. The authorities had not consulted San Isidro residents when they made this decision, nor was the community informed about any sort of long-term plan. While Zenaida explained that the authorities did not force them relocate, the community felt that they had to move because they were not presented with any alternatives.

The local government provided Zenaida and her family with some wood, and they built a small house alongside about 40 other families. More than four years later, they all remain there. What was meant to be temporary has become permanent.

Zenaida misses her old home and explains she is still affected by the hasty relocation. Life at the site is hard. Water access is sporadic. “[Sometimes] it’s only for two days,” she said. “Sometimes we have it just once a month. In August [2025], we went the entire month without having access to water. We are lucky if it rains.”

Accessing water is not the only challenge. The steep road makes it impossible for her to move independently, cutting her off from the rest of the village. If another storm comes, the evacuation center is down the same inaccessible road. “I am afraid for my own safety because of my disability,” she said.

“The mangroves protected me.” – Hasael Compra

In Del Carmen, the island’s largest municipality, Hasael, a 44-year-old fisherman with a physical disability, has fished since he was 12. The area is home to the Philippines’s largest mangrove forest —a vital area for biodiversity and conservation efforts that also helps protect communities from storm surges.

When Hasael was a child, he used to help his parents earn a living by climbing coconut palms, selling coconuts in the market, and using the income to buy food. At age 9, he fell from a coconut palm and sustained a spinal cord injury that left him unable to climb. He then turned to fishing as a way to support himself and his family.

Typhoon Odette struck while Hasael was at sea: “I almost drowned because of the strong wind and waves. I was really scared, my boat almost capsized. I changed my route and went to the mangroves. [They] protected me against the strong wind and strong waves.”

Eventually, he managed to reach the shore: “There were no people around; everyone had already evacuated. I first went to my house, which had been destroyed. I then came here to my parents’ house and saw they hadn’t evacuated. We sheltered together in this portion of the house.”

FIRST: Hasael in the kitchen of his home in Siargao, Philippines, 2025. © 2025 Camille Robiou du Pont/Human Rights Watch; SECOND: Hasael’s parents in their home in Del Carmen, Siargao, Philippines, 2025. © 2025 Camille Robiou du Pont/Human Rights Watch

Lacking a vehicle or support of any kind, Hasael and his older parents were unable to evacuate.

They sheltered together in the only structure of his parents’ house that was still standing—a room made of concrete: “The water level in this house came to our hips, the roofs of the house were blown away, but because this room is made out of concrete, it wasn’t destroyed.”

Later, Hasael discovered that his own home had been “carried away by the water.”

After the typhoon, the government declared the coastal area a “No-Build Zone.” However, with no alternative housing offered, Hasael rebuilt part of his home with salvaged, makeshift materials at its original location. “I didn’t receive any support to rebuild,” he said. “The government gave us food and relief but no money.”

To implement the No-Build Zone policy, the local government has been planning a permanent relocation of the communities living in Del Carmen’s coastal area, including Hasael and his parents. However, to date, authorities have made insufficient efforts to inform or consult the community. Hasael has heard only rumors about planned relocation.

Because of his livelihood, Hasael is adamant about not leaving his home, fearful he would be relocated far from the ocean: “I’m a fisherman – I basically live on the ocean. Because of my disability, I cannot work as a laborer and because I didn’t go to school, I also can’t get another job. Being a fisherman is the only thing I know how to do, and I’m good at it.”

Hasael has seen climate change erode his livelihood over time, as rising sea levels and increased ocean temperatures make storms more intense and unpredictable. He said these changes have reduced fish stock: “Before I would earn 500 pesos (US$8.50) in a day but now it’s 100 or 200 pesos. I feel like there is nothing there [in the ocean] anymore. The water is hotter and the fish are no longer there.”

For Haseal, fishing is not just his livelihood. “It’s my skill, it’s my life,” he said. “When I’m in the water [fishing], it doesn’t matter if it rains or it’s sunny or windy, regardless of the weather, I like being in the water.”

Relocation to an inland site far from his fishing grounds threatens more than his income – it threatens his identity.

“I want to be there.” – Johanna Marie Pacle

Johanna Marie Pacle is a young woman with a physical disability who lives with her family in the coastal area of downtown Del Carmen.

Born with a rare condition that affects her limbs, she loves to dance and is a content creator with thousands of followers on TikTok, where she shares dance videos. Johanna dreams of going back to school but said she gave up that opportunity so that her brothers could continue their education. Her father works as a laborer in the port carrying tourists’ luggage, and her mother works in Metro Manila as a housecleaner, making it financially difficult for the family to support her studies.

Like Hasael, she has lived her entire life in the coastal area now designated as a No-Build Zone, in a stilt house sitting above the water that can only be reached by crossing narrow makeshift bridges.

To carry out the No-Build Zone policy, local authorities plan to relocate her community to an area they say is safer.

Like many others in her community, Johanna has not received any information about the relocation plans. “The government has said nothing to me or my family” she said. “It’s just the rumors we rely on.”

While Johanna feels deeply attached to her current home, she is open to the idea of relocation: “Maybe it would be good for safety reasons so no one is harmed. If someone came and told me [we need to relocate], I would agree. We don’t even know when the next storm is, and it would be nice to be somewhere safe.”

What matters most to her is being consulted: “Whatever plan there is, I would like to see it. As a person with a disability, I’m used to not being consulted. If the government decides to organize a public hearing, I want to be there.”

Johanna loves the mangroves surrounding Del Carmen. “The first time I went there, the moment I saw the mangroves, I felt peace. … [I]n case of a tsunami, they will protect us.”

“I also need to make an income for my family.” – Mirasol E. Escanan

Mirasol Escanan was born with a condition that affects her limbs and proudly identifies as a person with a disability. She works in the tourism sector as a port treasurer. She also lives in the same community as Hasael and Johanna and is the current president of the Association of People with Disabilities in Del Carmen.

Mirasol met her husband at a party more than two decades ago. Years later, her husband had a stroke which led to a physical disability. She was working in the United Arab Emirates when Typhoon Odette hit. Because their children were young, the neighbors had to carry her husband to safety.

In 2025, Mirasol’s husband had another stroke, and lost the ability to walk or speak. Today, Mirasol is the sole provider for her family of four boys and her husband.

“I want to be safe with my family,” she said. “For that, I would accept the offer to relocate. But I would also need to make an income for my family. Either I would need to have transport to commute to my current job or receive support to open a small store at the relocation site.”

Relocation would also mean leaving behind the friends and neighbors that Mirasol relies on for daily support. For her, safety is inseparable from access to work and community: “I need to work here, my family needs my income.”

---

People in communities across Siargao island, including those with disabilities, bear the impacts of climate change and are not adequately consulted by authorities planning relocations. Consultation and access to information have been very limited and, for people with disabilities, relocation sites are often inaccessible and far from their livelihoods and support networks. These stories highlight what people with disabilities are seeking: to be consulted, to be safe, and to stay connected to their work, communities, and identities as climate change makes storms like Typhoon Odette stronger and more common. As authorities continue to develop relocation plans, the question of whether or not they will give local communities a voice in the process remains unanswered.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the individuals who shared their experiences with courage and dignity. Their contributions made this research possible. We recognize the challenges they and their communities face and their hope that their accounts will contribute to safer, rights-respecting relocation efforts.

Research and writing were conducted by Emina Ćerimović. Camille Robiou du Pont took photography and video. The feature was edited by Samer Muscati and Mya Guarnieri. Erica Bower participated in the field research and provided substantive edits and specialist review. Carolina Jordá Álvarez produced geospatial analysis in support of this research.

Art direction and development by Maggie Svoboda with support from Travis Carr and Malena Seldin. Web development by Christina Rutherford.

The feature was reviewed by James Ross, Holly Cartner, Maria Laura Canineu, Juliana Nnoko, Julia Bleckner, Sylvain Aubry, and Byrony Lau, and prepared for publication by Audrey Gregg.

We extend special thanks to Arvhelynn Litang and Erwin Mascarines for interpretation support. The local government in Siargao helped us in identifying interviewees and Del Carmen Mayor’s office provided us with documentation.

Human Rights Watch also thanks the non-governmental organizations and organizations of persons with disabilities that shared their knowledge and expertise, including Karla Hanson, Shiela Aggarao, and Jun Bernandino at Life Haven.

Thank you also to Mathew Reysio-Cruz, Carlos Conde, Jonas Bull, Nat Slater, Ginbert Cuaton and Yvonne Su for their early support in scoping this project.

Published on February 19, 2026.